Food forest - second update: 3 years

My updates are a bit few and far between. Things move a bit slow here, at human pace, not machine pace. March 2022.

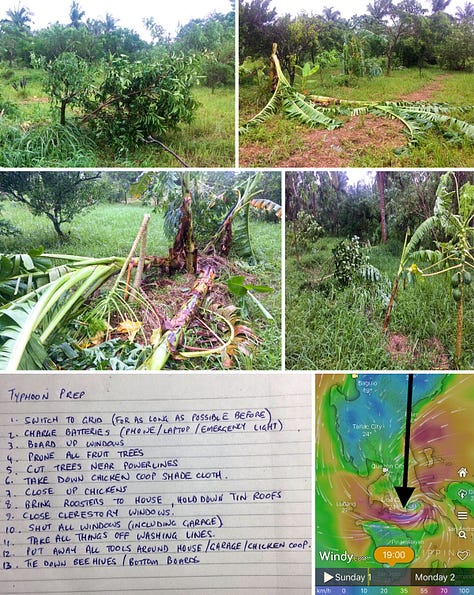

We've had a very good past 18 months. We were only hit directly by one typhoon in 2021 and damage was luckily minimal. We lost a lot of bananas but only a few fruit trees. 2020 saw us get hit directly by three typhoons in the space of 17 days. You quickly learn to appreciate life when you see the devastation and loss of life that these typhoons cause every year here in the Philippines. Complacency when a storm warning is issued is risky; some have gone from storm to super typhoon overnight.

So our food forest is now a very wonky food forest with trees leaning wildly out of their neat contoured rows. We've learnt never to try and correct these wonky trees in the days after the typhoon; they usually naturally correct themselves and continue to flourish. The good thing is they should be easier to harvest now they grow closer to the ground.

We continue to evolve in the way we manage our 2.5Ha property. Learning from our mistakes, responding to changing climate, living with the annual threat of typhoons, and developing our own ideas of what we consider a good life; slower-paced and simpler. It’d be nice if “simpler” meant “easier”, but it’s like running a marathon. It’s simple; you begin at the starting line and run to the finish. But it’s not easy. We’re continually managing our expectations to fit in with this and after three years we’re finally no longer in a continual state of feeling overwhelmed by all that we “need” to do.

I now prefer working at a slower pace, with a keener eye on learning the ecology of this place. I believe by concentrating on restoring water and soil that all good things will follow. I try to question what I’m doing as often as I can (lately it’s a lot, too many sleepless nights).

Being a part of western civilisation inevitably means pretty much everything we do causes harm to the natural world. My first question was how can I stop doing harm? It’s overwhelming to consider. But we need to start somewhere. How can I do less harm? Anna from Frozen 2 sings:

“You are lost, hope is gone, but you must go on and do the next right thing,”

“Take a step, step again, it is all that I can to do the next right thing.”

Just keep doing the right thing, and after that, do the next right thing. I think the most important “right thing” I can do here is restore the land's ecological function.

The next question I asked myself, can I have green grass all year round?

This was easy. Scything is basically a poor imitation of managed grazing, without the animal poop and impact. The best advice I got when starting (thanks Nick Ritar) was not to introduce livestock too early. So scything was a great substitute and now I have an abundance of grass which has turned out to be one of our biggest assets. The regular scything of the grass at an optimal time in its growth stage, then letting it rest and recover, helps improve the soil which helps with soil’s water holding capacity. This means that when it rains, the water that hits our land gets absorbed rather than running off into the river at the end of the property.

Keeping this moisture on our land for as long as possible means continued plant growth all year and keeping our soil’s microbial life going for longer into the dry season.

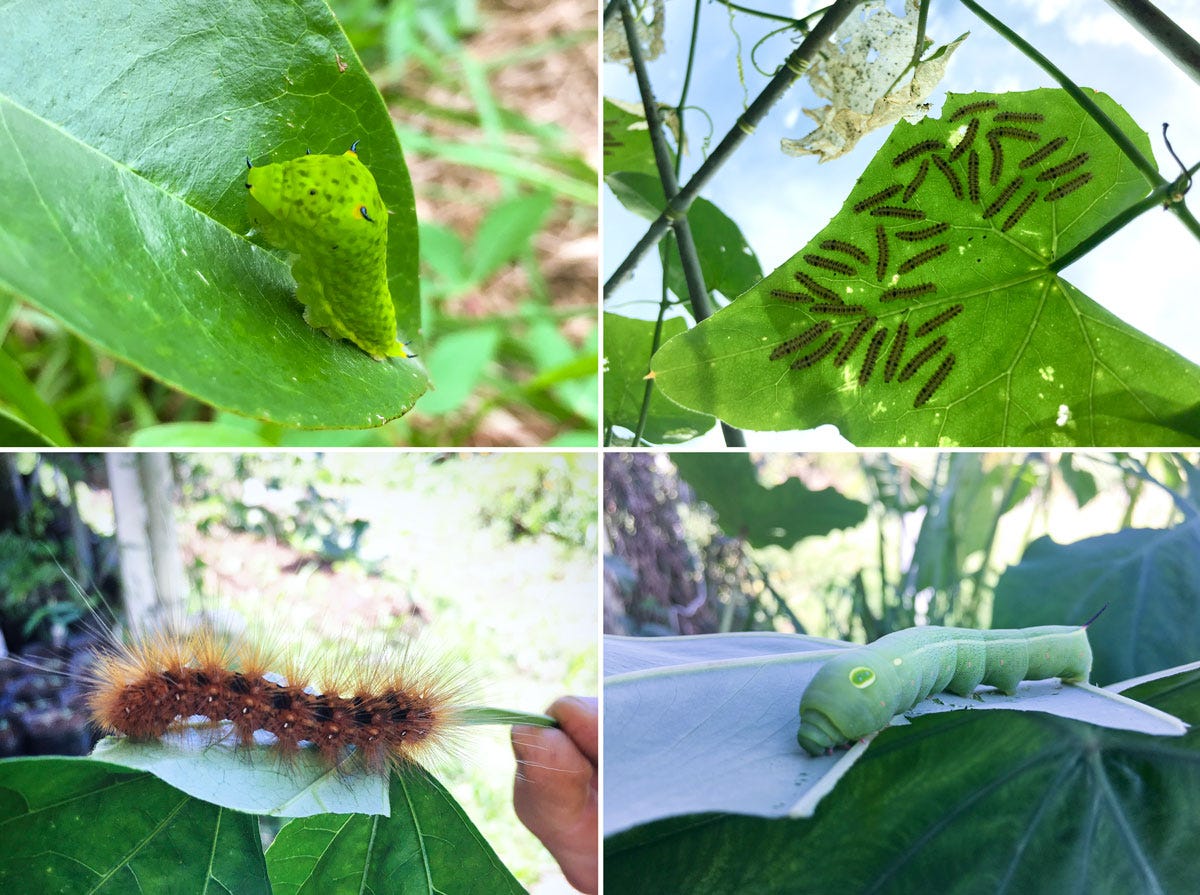

My new question is can I increase the number and diversity of life on our land?

This one is always ongoing. Often it’s a matter of me NOT doing things that helps. For instance; at this time of year, when growth is a bit slower, I’ve stopped scything. I’ve let all the grass and ground cover weeds go to flower and grow long. This provides ample food and habitat for insects and insect pollinators. It also coincides with the start of honey flow for our bees. With abundant bug life there’s plenty of reason for birds to drop in for a meal, and possibly be enticed by the cover of the grass to build their nests and raise their young (all going well until locals jumped our fence to cut the grass for their cows). More bugs means more frogs, lizards and snakes also. I’m hoping with this approach we can attract some larger birds of prey back to the property to help with our rat “problem”. We’ve spotted a pair of hawks flying out from our river area, and we used to have a grass owl that we’ve sadly not seen or heard for over a year.

With the typhoons, there’s always an abundance of fallen branches and old trees knocked over. As I use hand tools, often a lot of the wood gets left laying in the place it fell for half a year or so. If I can, I break it down enough that the wood is in contact with the soil and that it doesn’t cause problems when scything. After a few months the wood is much easier to break up and inoculated with various lichen and fungi. I transfer this along my tree contour rows where it very slowly continues to decompose, providing habitat for insects and small animals, and importantly holding a lot of moisture and keeping microbial life alive. For me, this is the most important mulch you can use. By accelerating the microbial biodegredation of the fallen wood it becomes less of a fire hazard, instead an important benefit to the land.

We noticed a drastic decrease in bee numbers at this time of year, despite the wild weed flowers everywhere. So we installed over a dozen native stingless bee hives (thanks to our wonderful friends Beemerry and Jerry in Lipa). I'm also considering leaving permanent nature strips that will remain untouched to provide habitat for insects that need longer periods of dormancy such as fireflies. We’ve always had very low firefly numbers and it’s something we may be able to assist simply by stepping back. I’m unsure of how to go about the permanent nature strips though; should I still occasionally have our sheep graze the nature strip lightly so not all the grasses over-rest, or completely fence it off?? (advice please!)

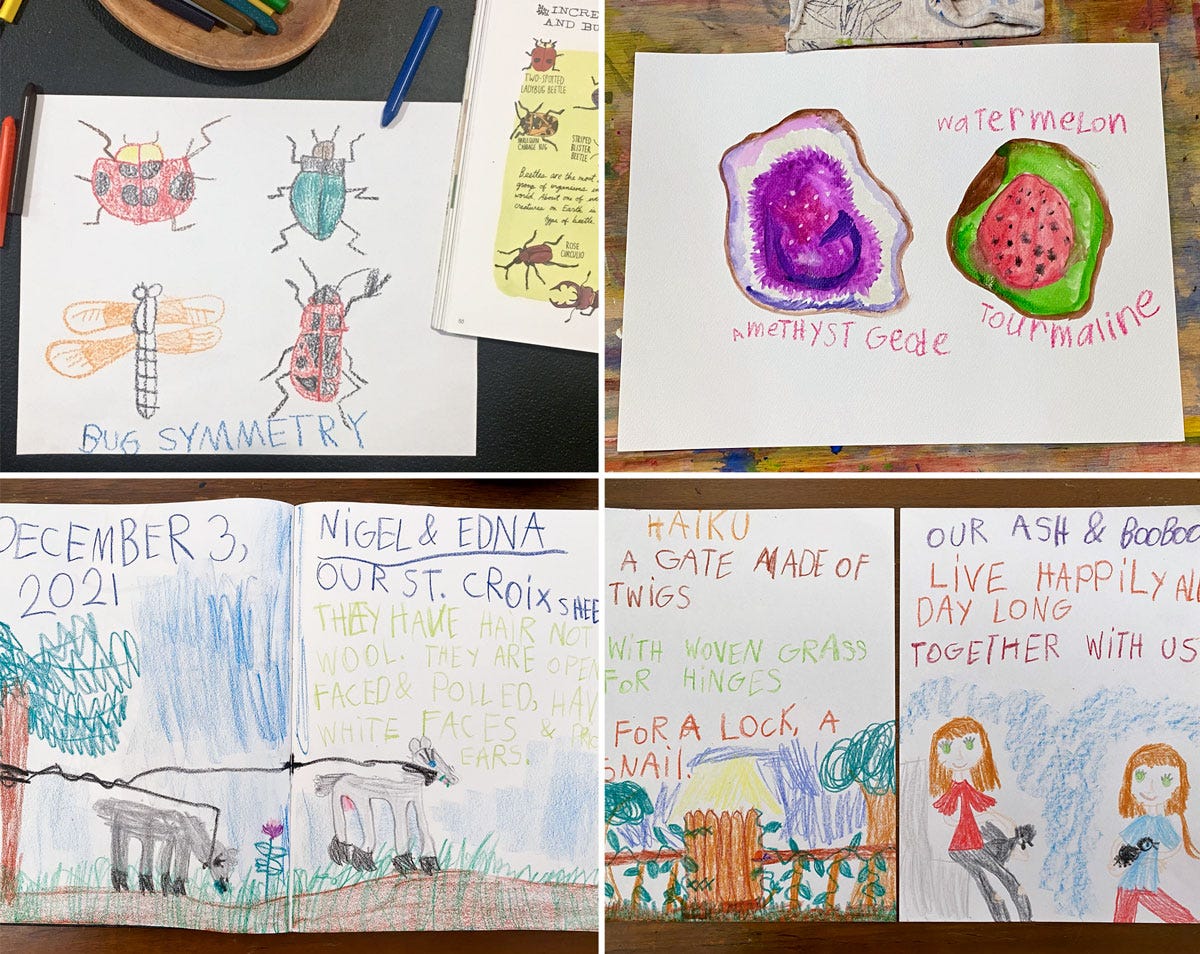

We recently added four sheep to our farm; Edna, Nigel (or “Nige” for short), Betty and Kylie. I’m slowly moving them around the north side of the property where there’s an abundance of extremely fast guinea grass growing. These grasses were all introduced years ago and difficult to remove but have become incredibly important to me. Unmanaged, it can degrade the soil and become a fire danger. With regular scything it’s increased the water holding capacity of the area and is a fantastic long lasting mulch. Scything it is heavy work so letting the sheep into it helps me out in a big way. Sheep, as Walter Jehne says, are compost heaps on four legs, so I increase fertility and get meat out of it at the end. Sunlight into meat.

We got more poultry for our farm; Guinea fowls, Buff Orpingtons and ducks and a few rabbits. These are also rotated slowly around the property, always keeping a close eye on the impact they make. Our native chickens, which resisted any efforts on our part to contain them, roam freely in and out of the electric fence areas, occasionally breeding with our imported breeds, disappearing for weeks and reappearing with a clutch of chicks. We started with only a pair from our next door neighbour and now have over two dozen. They pretty much feed themselves and have so far made little impact on the young trees with all their scratching and digging. We eat nearly all the roosters, as they can be quite aggressive and will probably start eating hens if their numbers become a problem.

One thing we’re slowly working towards with our poultry is eventually stopping all imported feeds. It’s also a guiding inspiration I’m working towards with most of the farm, a sort of zero-input agriculture. All well-made and repairable hand tools (no reliance on fossil fuels for gas guzzling grass cutters and chainsaws), no imported fertilisers (fertility created with animal rotations and grass-fed mulch), all our own rainwater and power, seed saving to create resilient plants genetically adapted to our location. We’re still a long way from this, we still buy most of our food but it’s something we keep in mind.

We planted nearly all native trees last wet season and most rapidly outgrow anything else I've planted here. I’m a new convert to understanding the essential role of natives in ecosystem restoration. We also get a lot of saplings introduced by birds and bats and with scything, it’s easy to spot them and let them grow out. The Philippine Native Tree Enthusiasts group on facebook has been a huge help in identifying these, and without fail we’ve been impressed by the diversity gifted to us.

We will be concentrating on planting a lot more natives this coming season. Last year’s were mostly tall hardwood timber natives with some flowering trees. This year I’ll try to get a lot more smaller bushes and shrubs and plants we can easily use as forage for our animals.

The original food forest design was planned around full size fruit tree spacing. I'm now introducing new tree rows between them with natives. With the number of typhoons we get I've realised the job of planting trees will never finish. It seems to me, the survival of our little future forest is a numbers game. I may as well pack in as many trees as I can and hopefully create a shelter belt from the winds and also from the sweltering summer temperatures.

A massive benefit of the agroforestry system is that there’s always shade for the animals which is essential in these hot summers.

The food forest area was originally planted with syntropic principles in mind but I quickly found that the workload was more than I could handle. It was a stretch to imagine I could manage it over the 1.8Ha of planted area by myself. As a result the tree growth is nowhere near what you can see in successful syntropic systems. But if I walk around the farm after a homemade ginger wine or two, I can still manage to be pretty proud of how it’s all going. This season, I want to introduce more vines and flowering understory native shrubs depending on what we can find at the nurseries.

I’ve made some attempts at alley cropping between tree rows but so far it’s been disappointing. I’ve experimented with sorghum (both white sorghum which we also use in our gluten free baking and red which is more for livestock), corn (sweet corn, popcorn and flint corn), Adlai (Jacob’s tears). On a smaller scale in deep beds I’ve also grown local millet, amaranth, black sesame and chia in order to save seed for future attempts on a larger scale.

The biggest failures were no-till, using a hand jabber to plant amongst recently mowed grass. Not much came up. With time and more animal fertilisation and improved soil I hope I can make it work. The best results were from light tilling with addition of lots of compost. Our healthy rat population often gets to the ripe grains first. Despite these setbacks, I still save seeds from the healthy plants and will try some more this year. Doing all this by hand, you quickly realise how inefficient grains are to perennial tree crops. But my stupidity will persist while I have the youthful energy to spare (47 y.o. already!).

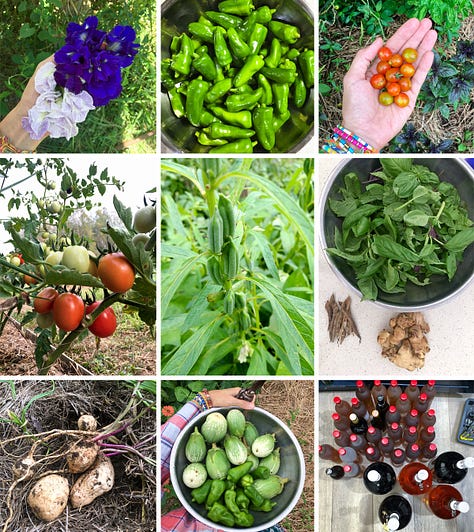

Most of the fruit trees I planted in the first year are now well over head height and we’ve had fruit from a few already; macopa (wax apple), atis (custard apple), lemon, calamansi (Philippine lime), aratiles (cotton candy berry), pomegranate, acerola cherry, mulberries, guava. New ones are flowering now so hopefully this could mean fruit in the next year or so; cashew, coffee, santol. We get bananas fairly regularly but my management of the trees is pretty poor, hopefully I’ll improve on that and also plant a lot more this year.

Our little veggie garden is probably our biggest weakness, we don’t make enough time to tend to it and it quickly gets overrun with tropical grasses if we turn our heads too long. While we mostly grow local veggies acclimatised to our area through seed saving, we also continue to try growing our favourite foods from afar. We had a fantastic amount of broccoli in the works, but caterpillars got to them as we hadn’t planted flowers in time to distract them. Never mind; we’re hopefully going to have an awesome amount of butterflies this summer.

We grow a lot of local beans, both to eat green and dried for saving and storing. We grow luffa for our own dishwashing sponges and also as a veggie if we get to it before it goes bitter. Local climbing beans like bataw and passionfruit cover our trellis, providing great shade and passive cooling for the house. We love growing chilies and also foraging for the wild native chilies that the birds spread everywhere. We grow wild cherry tomatoes and plant them all over the place for quick snacks for our hungry daughters. Over the three years we've planted hundreds of pumpkins and every year they now return by themselves, giving us enough to fill our freezer, a simple addition to many of our meals. We grow a lot of ginger for fresh use and turmeric to dry and store. A lot of sweet potatoes for both the tuber and leaves. After thunderstorms we forage for the delicious wild mushrooms that pop up around the many termite and ant hills. We grow roselle, which now self seeds, for jams and teas. We collect the reishi that is abundant here and make into tinctures.

We have double-dug beds and use heavy mulch, regularly topped with rabbit poop. Despite this, the soils still get compacted and hard. We can neglect to water for weeks because of the deep beds, but this is probably a big limit to us being more successful. Also a big limit in the food forest. We have plenty of rainwater stored and available but distributing it is time consuming without installing more plastic piping and irrigation hardware and pumps.

So that’s my update on where we are at, I’ll try to do some more detailed posts expanding on a few things in the future. I wouldn’t really call what we’re doing farming since we’re not trying to make a living from it, rather we are trying to live more within our means, focusing on home economics. We try to be an example to our girls, homeschooling and unschooling, and when we say family is the most important thing, we practice it by spending time and listening to them as much as we can. We believe kids that love and understand nature will grow up to look after it.

Some more things:

Donella (Dana) Meadows lectures on Systems Thinking. Long but very worthy of a listen. We all need to become systems thinkers; children are great systems' thinkers but our Western education with its emphasis on linear and binary thinking knocks the ability out of use:

Ecological Knowledge and the Biosphere Crisis: A facebook group which is a learning platform for spreading ecological knowledge. Probably the biggest influence on the path we’re moving towards on our land: https://web.facebook.com/groups/666839537170062/

My friend David's great essay about plants. David and his wife Karn continue to be a big inspiration to us:

“For all his suspicions of having achieved divinity, man is a creature of this earth, completely dependent upon the interplay of all forms of life. For his agriculture to endure to his benefit, it must strive for harmony with its natural surroundings: No dairy cattle or pigs in the arctic, no plows on the tundra, no biocides to protect exotic crops. It must be a gentle agriculture, one of variety and one that is not too efficient."

---- John J. Teal, Jr. 1972

Hi Leon, thanks for the update. It is funny that I am in Malaysia but our journeys have so many similarities. We tend to a 2 hectare homestead since four years ago. Have two kids, goats, apply some syntropic (our own version) combined with permaculture. No typhoons though! Do keep writing. I write at intotheulu.com but havent been writing much with two kids. Also i am unlearning a lot of stuff and going through a transformation thats hard to verbalise as yet. :)